I

In September 2021, after spending two weeks with family in and around Brussels, I boarded a near seven-hour train ride to Berlin. I arrived at Charles de Gaulle airport two weeks earlier, after moving out of my room in Philadelphia and putting all of the things I had accumulated over five and a half years into my parents’ basement.

This trip was intended to be a much-needed getaway from both Philadelphia, a city I grew up just outside of and lived in for over 5 years, during and after undergrad. I also wanted to leave Instagram for all the usual reasons, and also because the overabundance of artwork on display is so compressed and mediated that almost no image can have a lasting impact. I felt stagnant; after a year plus of covid life, I desperately needed a change of scenery.

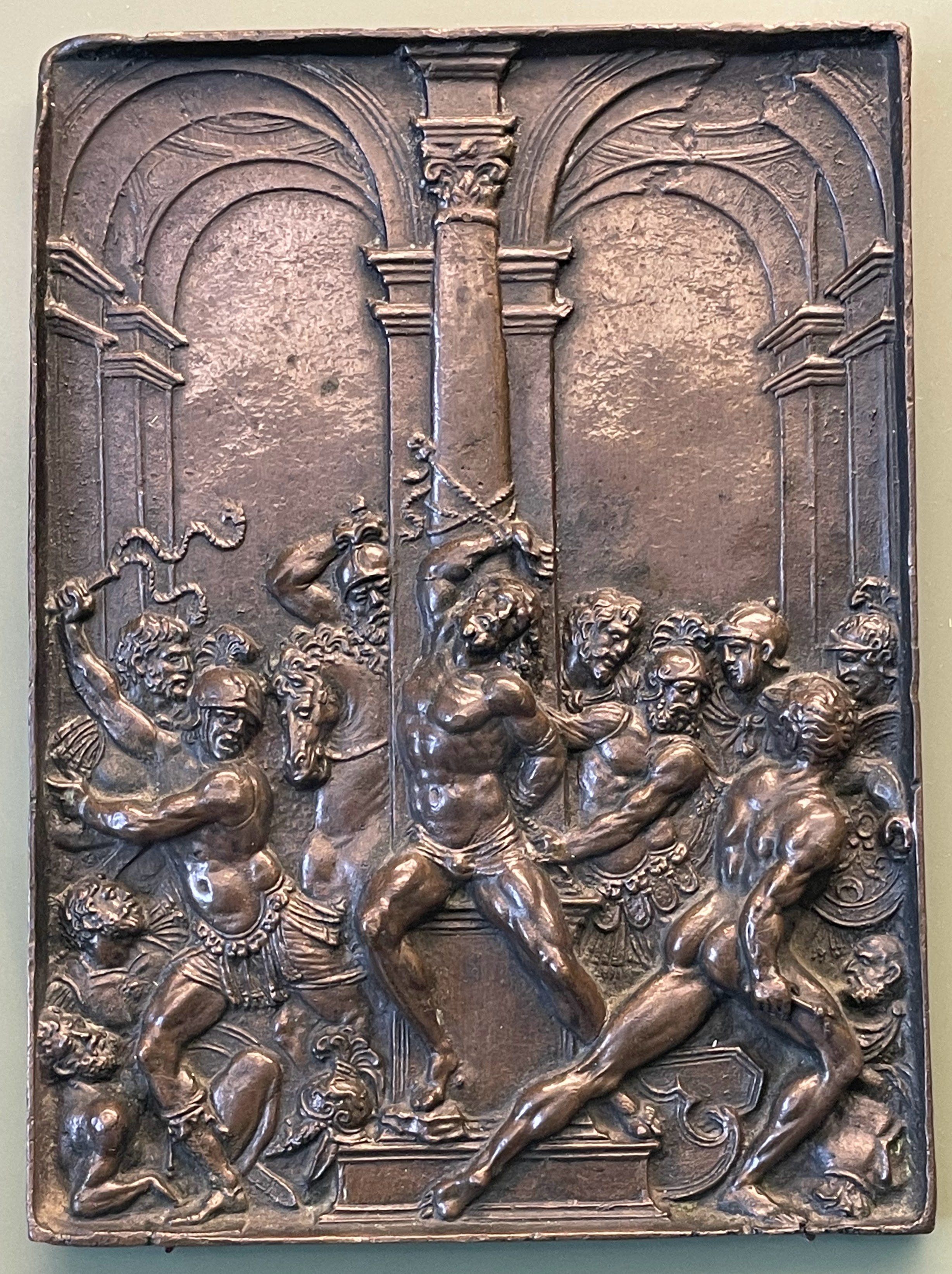

The museum that had the most impact on me was the Bode Museum on Museum Island in Berlin. Arriving only an hour and a half before closing, I walked quickly to get a survey of the work in the galleries. so much of the work, especially the smaller ones, captivated me. The artists’ powers of observation and drawing, knowledge of anatomy, dramatic storytelling ability, and mastery of their materials were evident.

Unlike most of today’s artists, they had the advantage of beginning their apprenticeships in their early Adolescence and of having a set of stories that they would discover how to tell in their own way. This allowed the craft of drawing and observation to be honed and pushed, creating some of the most famous works in the European canon.

Once the Bode closed for the evening, I left on an aesthetic high. I walked over the Spree river to the KW Institute, one of the leading contemporary art institutions in Berlin. In the courtyard that preceded the entrance, cool-looking twenty and thirty-somethings milled around with an air of aloofness and exclusivity. Inside was a wide array of installations, sculpture, video work, and various other artworks that could be loosely categorized as conceptual. After going through all of the floors and rooms of the building, I felt disappointed. Very little of what I saw drew me in or excited me. Was I alone in feeling this way? Did other viewers feel something I did not? Was there something missing inside me or inside the artwork, or both?

II

There were two particular works that I had to see after leaving germany. The first was the Ghent Altarpiece, the crowning achievement of Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, the first painters to use oil paint to its furthest extent in Europe, paving the way for the widespread use of oil paint across the continent.

The altarpiece came in all shapes and sizes and often had a central panel or composition with wings on either side that would open to reveal the elaborate central panel on worship and holy days. Because of this, the exterior faces of the wings were also painted, usually with portraits of the wealthy patrons who commissioned them: a way to curry favor with the god and possibly atone for sins. They were also often embellished with scenes from the life of Christ. The Ghent Altarpiece is no exception.

I finally arrived at the altarpiece after entering the church and making my way to an area in the left rear, through stunningly modern automatic glass doors, up a flight of stairs, through a set of bronze automatic doors, pass the Rubens, into the open area of the second floor and to the left. Upon entering the tall open room, one is confronted with an enormous glass and steel bulletproof, climate-controlled case, with the Altarpiece grandly standing inside.

My first thoughts were RED, GREEN, BLUE. The depth, richness, and harmony of the color of the landscape and the robes of the figures sang out, echoing the angels above. I caught my breath.

On the bottom central panel, I surveyed the four groups of figures, every face detailed, and every fold of cloth elaborately rendered. In the center, the lamb on the altar, blood flowing, like a fountain for a wound in its chest, into a golden goblet. Further back, rolling hills transitioned from a rich forest green to pale blue, capturing the effects of atmospheric perspective. At the top of the panel, the dove spread its wings, shining golden rays of light onto all in the scene.

Looking up at the top register of the work, was the deity, a fairly young and handsome God the Father ruling with a scepter in hand. Flanking him are Mary and St. John the Baptist, but the real attraction is the angles. The two groups of angels are then flaked by Adam and Eve (respectively left and right). The angles’ pale faces serene, focused, and pained all at once. Their liturgical robes are embossed with gold, their heads adorned with crowns of gleaming stones. My attention turned to Adam and Eve who stand in stark contrast to the angels. Both figures are nude and highly naturalistic, standing in a niche with a dark background, as if statues just come to life.

The dazzling effects of the painting had been achieved meticulously through precise underdrawings and thin, slow-drying layers of color. Had it not been for Van Eyck’s interest in the natural world, revolutionary use of oil paint, attention to the smallest details and enduring patience, his masterpiece would not attract the swarm of visitors it does each year.

I wanted to stay there all day but found that my eyes could only take so much intensity. I returned two days later with Kanye West’s then just-released album Donda, flooding my ears. The choral, hymnal quality Kanye has sampled and mastered over the years along complementing the atmosphere and work almost too well. The anachronistic collaboration harmonized and pushed me to look at the space around the work, taking in the entirety of the radiating chapel, with its sculptures and stained glass windows, and also made with think about how the sound made by a Black American choir would travel through and fill up the space. A mixture of wonder and melancholy welled up inside of me. This painting, made by two brothers over the course of a decade over 500 years ago, has, in many ways, not been surpassed.

III

After packing my bags and saying goodbye to Ghent and it's beautiful stone streets, humble alleyways, and winding canals, I took the TGV into Paris to see the second piece I had to see, Arc de Triomphe Wrapped by Christo and Jeanne Claude. Upon arriving, I took the subway to Charles de Gaulle Etoile and walked up into Place Charles de Gaulle, an enormous roundabout with the Arc de Triomphe wrapped in a silvery fabric at its center, framed by red and yellow cranes and the bright blue sky. L’Arc de Triomphe Wrapped would open in just a few days.

The artists behind this monumental work, Known together as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, were born to two very different families in Europe on June 13, 1935. They met in Paris in 1958, fourteen years after Paris was liberated by the Allied Forces and eight years until the Arc de Triomphe would be bleached and made to look the way it does today. Over the course of their seven-decade career, Christo and Jeanne-Claude created installations on the largest scale that more often than not, used fabric as their primary physical material. Jeanne Claude died in 2009 and Christo followed her in 2020. Arc de Triomphe Wrapped was to be their last temporary public work.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s works took anywhere from several months to decades to complete. There were logistical and political hoops to jump through, material ecological studies to be conducted, governmental and private property owners to be convinced. The grand majority of their realized works have been financed through the sale of the artists’ studies, preparatory drawings, collages, scale models, early works, and original lithographs. L’Arc Wrapped was no different.

Wrapped changed with the weather and rippled in the wind. It breathed and used its seductive, quiet breath to beckon people in. It changed from different angles, with different weather and times of day and by how many people were by it. Sunrise and sunset were as magical as you could imagine. Under a cloudy gray sky, however, where it mesmerized as its own hues and values seemed to fade in and out of the surrounding sky, was perhaps the most interesting.

I spent one week sleeping in an apartment a few blocks down and around the corner from Wrapped. The silver-blue monument, tied together with sturdy red ropes, seemed to sit at the center of the world. It felt like watching Squid Game or Game of Thrones. It seemed like everyone was here, watching and participating, even if that wasn’t the case.

The Ghent Altarpiece and L’Arc de Triomphe Wrapped provided a foil for the Instagram experience and the way I had felt at the KW. These great works felt enduring and alive, like a religious text or a great novel. They told me about the merits of slowness, endurance, and dedication to craft. Through these attributes artists create work that pulls in a lasting public, bringing us together and telling us many things about ourselves that can only be articulated through specific scale and material. That reminder for me, is always necessary.